Africa’s financial relationship with China has entered a new phase. For the first time in decades, many African countries now send more money to Beijing in debt repayments than they receive in fresh loans.

New analysis from the ONE Data initiative confirms the shift. It shows that China has moved from being a net provider of finance to a net receiver from developing economies, especially across Africa.

Over the past decade, new Chinese lending to poorer nations has dropped sharply. At the same time, repayments on earlier loans have continued to rise. As a result, financial flows have reversed direction.

According to the report, Africa recorded the most dramatic change. Between 2015 and 2019, the continent received about $30 billion in net financing from China. However, from 2020 to 2024, that figure flipped to an outflow of $22 billion.

That change represents a $52 billion swing in just five years.

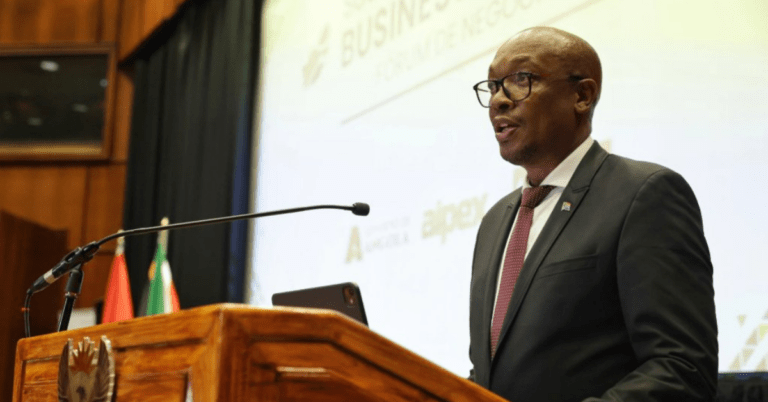

David McNair, Executive Director at ONE Data, explained the shift clearly. China now lends less, but old debts remain active. Governments must service those loans. Consequently, money flows outward instead of inward.

Meanwhile, global development finance has not disappeared. Instead, it has changed direction.

Multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and regional development banks have stepped in. Over the last decade, they increased net financing by 124%. Today, they provide 56% of global net development flows, worth $379 billion between 2020 and 2024.

This rise has reshaped the global funding map. Africa, Asia, and Latin America now rely more on multilateral lenders than on bilateral partners like China.

However, the outlook remains complex.

The data does not yet include changes from 2025. Yet early signs point to new pressure. The closure of the U.S. Agency for International Development and funding cuts from several advanced economies have already reduced support for developing regions.

McNair expects official development assistance to fall sharply once full 2025 figures become available. That decline could hit African economies hardest.

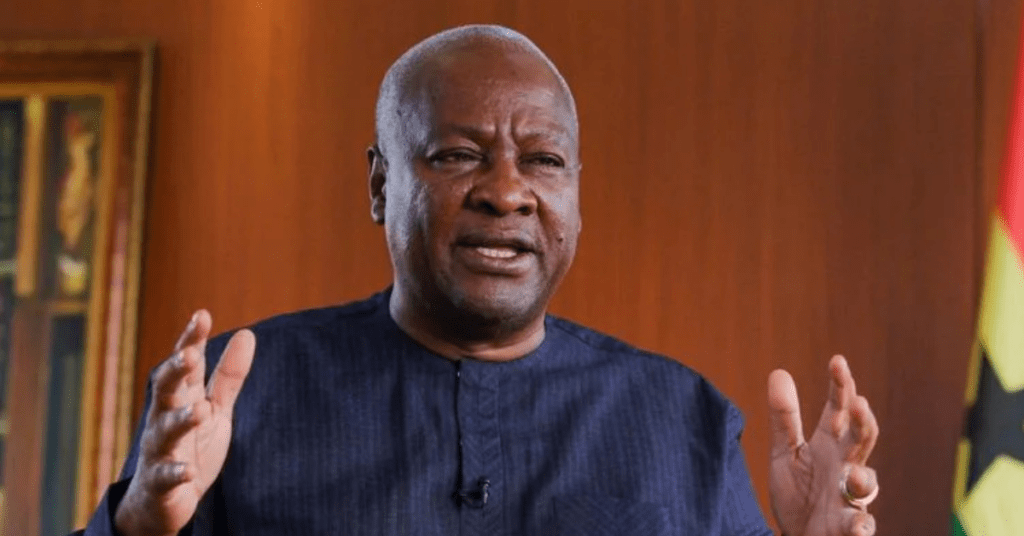

He described the trend as a “net negative” for the continent. Many governments already struggle to fund healthcare, education, and infrastructure. Less external support could deepen those challenges.

Still, he also noted one potential upside. Reduced dependence on foreign financing may push governments to strengthen domestic revenue systems and improve public accountability.

Beyond China, the report highlighted another shift. Bilateral financing and private external debt are also declining. Aid cuts from 2025 onward could accelerate this pattern.

Yet China has not stepped away from global infrastructure.

Separate research from the Griffith Asia Institute shows that Chinese overseas deal-making rebounded strongly in 2025. Deals linked to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) reached a record $213.5 billion.

Construction contracts accounted for $128.4 billion, while investments reached $85.2 billion. Notably, Africa emerged as the largest recipient region.

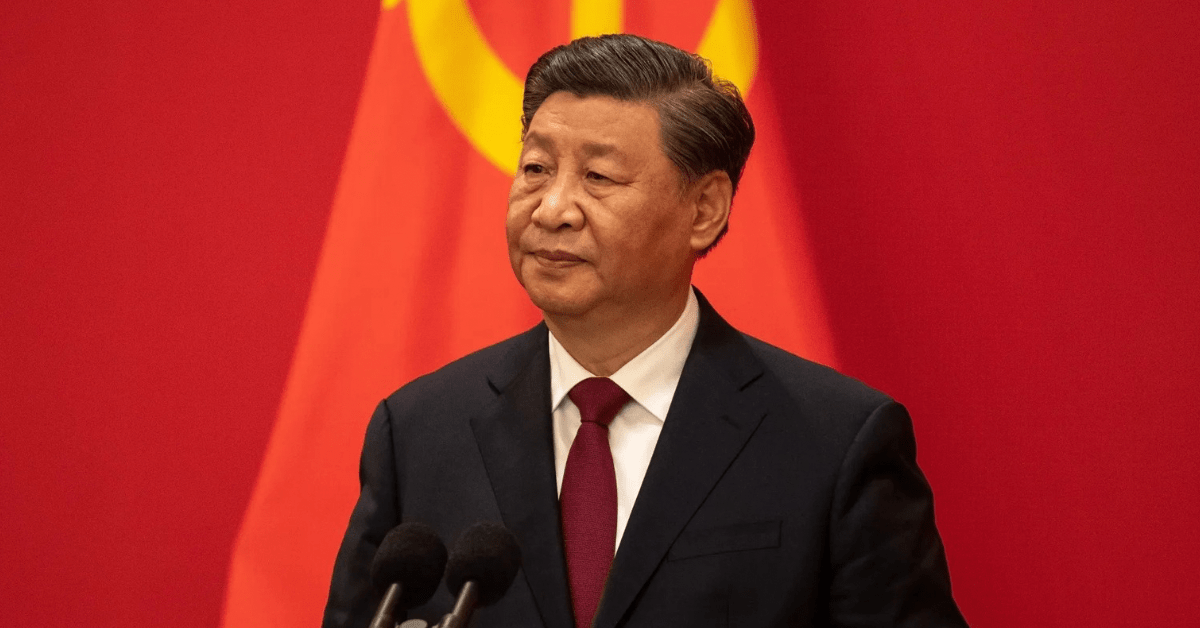

Launched in 2013 by President Xi Jinping, the Belt and Road Initiative aimed to link East Asia and Europe through roads, ports, railways, and energy projects. Over time, it expanded into Africa, Latin America, and Oceania.

Through this expansion, China has extended its economic footprint and political influence across the Global South.

Therefore, while traditional lending has slowed, strategic investment remains active.

For Africa, the message is mixed. The continent still attracts infrastructure funding. Yet debt obligations now outweigh new Chinese loans.

As global finance realigns, African policymakers face a new reality: balancing repayment pressures, shrinking aid, and the urgent need to fund development at home.