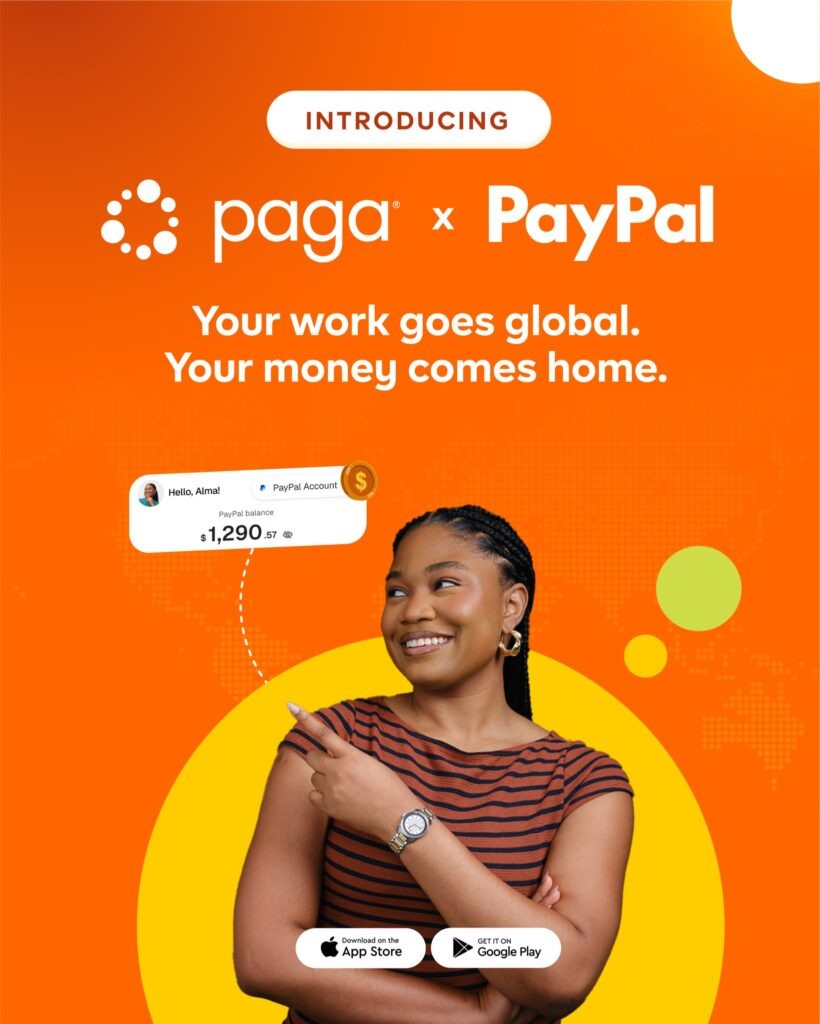

PayPal has returned to Nigeria after nearly two decades, re-entering Africa’s largest economy through a partnership with local fintech firm Paga, a move that has stirred both excitement and resentment among Nigerians who were previously shut out of the global payments platform.

The $55 billion payments company will now allow Nigerians to receive funds via PayPal and withdraw directly into their Paga Naira accounts, enabling freelancers, creators, businesses, and families to access cross-border payments without complex workarounds. Paga said the integration reflects its long-held belief that Nigeria would become a major force in global digital commerce.

PayPal’s Senior Vice President for Global Markets, Otto Abasi Williams, said the partnership was designed to help Nigerians get paid globally while using their earnings locally. He added that working with a local operator like Paga allows PayPal to build products that align with how Nigerians earn, spend, and grow their businesses.

Despite the renewed access, PayPal’s return has reopened long-standing grievances. Many Nigerians recall being abruptly excluded from the platform in the early 2000s, a decision that left freelancers and online merchants unable to access thousands of dollars in earnings. Over the years, critics have described the move as discriminatory and have questioned why Nigerians remained locked out for so long.

Unlock Your Chance to Get $500!

Unlock Your Chance to Get $500!

PayPal previously justified its withdrawal by citing high fraud rates and compliance risks. The company said its systems detected repeated cases of stolen credit cards linked to countries with weak identity frameworks and limited banking oversight, conditions it argued made financial fraud easier to commit and harder to trace.

Historical data shows that Nigeria did struggle with cybercrime during that period. A 2009 academic study published by the University of Warwick found that the FBI ranked Nigeria as the third-highest source of global cybercrime in 2007, even though internet penetration in the country was below 10 percent at the time. Nigeria also accounted for six percent of global internet spam in 2004 and recorded the highest median loss per online fraud case at $5,575.

However, analysts note that cybercrime has never been unique to Nigeria. At the same time those rankings were published, the United States accounted for more than 63 percent of global cybercrime perpetrators, followed by the United Kingdom at 9.9 percent, with Canada and Romania also ranking highly.

While Nigeria continues to feature on global cybercrime indexes, the structure of its financial system has changed significantly. Experts say the absence of digital identity and real-time transaction monitoring played a major role in PayPal’s earlier exit. At the time, Nigeria lacked the infrastructure global payments companies rely on to manage fraud at scale.

That environment has since evolved. The introduction of the Bank Verification Number system created a biometric link between individuals and bank accounts, while the National Identification Number expanded identity coverage beyond the financial sector. Regulators have also tightened Know Your Customer and Anti-Money Laundering rules and expanded oversight of payment service providers.

Data from the Nigeria Inter-Bank Settlement System shows that reported fraud cases declined from about 124,000 incidents in 2021 to fewer than 96,000 in 2023, even as digital transaction volumes increased sharply. Although fraud losses rose in nominal terms, the ratio of fraud to total transaction value fell, indicating that fraud has grown more slowly than the broader digital payments ecosystem.

Fintech executives argue that this shift explains PayPal’s decision to return through a local partner rather than as a standalone operator. Adedeji Olowe, founder of Lendsqr and chairman of Paystack’s board, said fraud figures must be assessed relative to total transaction volume, noting that smaller markets can appear riskier even when absolute losses are lower.

Nigeria has also become one of PayPal’s largest markets in Africa by volume, even during the years when the platform allowed only limited outbound payments from the country, suggesting strong latent demand for its services.

Still, trust remains fragile. Some users have already reported account limitations after their first transactions, raising concerns that PayPal’s risk controls may continue to create friction for Nigerian customers. Similar issues contributed to the failure of PayPal’s 2021 partnership with Flutterwave, which was also designed to ease access for African merchants.

Industry analysts believe adoption will ultimately depend on performance rather than sentiment. They argue that if PayPal delivers reliable service, competitive rates, and smoother user experiences, many Nigerians will overlook the company’s earlier exit. For now, PayPal’s return marks a significant moment for Nigeria’s digital economy, even as questions linger over whether the problems that drove the company away 20 years ago have truly been resolved.